Looking back to 2022 : Around the world

Published on Mar 02, 2023

The year 2022 has been rich in events and developments in relation to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8.7 to eradicate child labour and forced labour. In this retrospective, we looked back at the key landmarks of the year in specific countries.

Cambodia

Cambodia is the scene of a large-scale human trafficking ring designed to scam customers on the internet. Many people are allegedly tricked by an advert posted on social networks promising a well-paid job as a consultant in a customer service company, with no experience required. On arrival, they are deprived of their passports and forced to scam people on the phone or on the internet on behalf of criminal groups on a daily basis. Those who succeed in fulfilling the set objectives are rewarded with food, money or freedom. Those who fail to do so are beaten, tortured or sold to other groups (Source : Aljazeera).

Canada

A law is in the process of being passed and would require companies to be more transparent about the actions they take to combat child labour and forced labour in their supply chain. It should finally be enacted in 2023.

However, within the country, migrant workers face abuses and violations of their rights. These are mainly seasonal workers in the agricultural sector, whether they are in a regular situation or not. Several specialists have denounced the living conditions of migrant workers on farms in Ontario. According to one study, the poor housing in which many of these workers live may be a factor in their deaths. The quality of housing is very uneven; it is often overcrowded, due to a shortage of housing coupled with a boom in the agricultural sector (Source : Radio-Canada). Some suffer physical and verbal abuse, work long hours and handle pesticides without any protection (Source : Environbuzz).

In the Quebec region, a bill will be tabled in 2023. It follows several press articles showing children working in supermarkets and fast-food restaurants in particular. This situation is permitted because there is no law governing the minimum age for employment (Source : Radio-Canada).

China

In August 2022, the Chinese government ratified Convention 29 on forced labour and Convention 105 on the abolition of forced labour. This was a precondition for the EU to sign a bilateral investment agreement.

This ratification comes against the backdrop of China being accused by the international community of forced labour in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. UN experts concluded in a report published in August 2022 that it is reasonable to believe that forced labour of members of minority groups has taken place in the western Xinjiang region of China.

Elsewhere than in Xinjiang, other situations have been noted. According to an investigation by Channel 4 and The i newspaper, workers supplying clothes for a major international fast-fashion brand frequently work up to 18 hours a day, with no weekends and only one day off a month. Under a false name, a woman was able to infiltrate two factories. In one factory, workers are paid a basic wage of 4,000 yuan a month – about US$ 556 – for making at least 500 garments a day, and their first month’s salary is withheld. In the second factory, workers do not receive a basic wage: they receive 0.27 yuan, or about 4 cents, for each garment they make.

Egypt

Egypt has made a legislative breakthrough on child labour. On 17 January 2022, the Egyptian Senate approved Article 58 of the government’s draft new labour law. This article prohibits the employment of children under the age of 15. Employers will be able to hire children from the age of 14 for “training” if this does not affect their schooling.

In addition, every employer who employs a child under the age of 16 will be required to provide an identity document indicating the type of work performed. The government has repeatedly stated its commitment to eliminating child labour in Egypt. According to the latest ILO statistics, 1.8 million people are estimated to be victims of child labour.

The situation became even more dramatic in early 2022 when 8 children died on their way home from work. The children were among a total of 23 minors working on a poultry farm and returning home together in the village of Menoufiya. That night, they got into a truck to return home after finishing their work. As the truck tried to board the ferry, it made a wrong turn and ended up in the Nile.

United States

A US law banning products from China’s Xinjiang region came into force on 21 June 2022. As of its enactment, customs must systematically seize imports of goods with components produced in Xinjiang province.

The United States accuses the Chinese authorities of forcing members of the Uighur minority to work. The law therefore assumes that all products from this region are the result of forced labour. It is therefore up to companies that want to import products from this area to prove that no forced labour was used in their subcontracting chain.

In the United States, several cases of child labour were reported during 2022. The country has not signed ILO Convention 138 on the minimum age of employment. Exceptions to federal child labour laws allow children of any age to be employed in the agricultural sector. According to the Washington Post, in 2021 there were nearly 500,000 children working in the fields in the US. In other sectors where the employment of children is regulated according to age and working conditions, cases of child labour have been reported and companies have been convicted (Source: Slate). These situations have been found in fast-food outlets and manufacturing plants. The employment of children is sometimes the result of a lack of labour in these sectors of activity, especially as states such as Ohio and Wisconsin have proposed legislation allowing the employment of young people over longer hours.

India

In May 2022, a fire at an electronics manufacturing facility killed 27 people. The factory did not have the required licences to operate. According to data collected in 2021 by the global workers’ union IndustriAll, sectors such as manufacturing, chemicals and construction are among the sectors with the highest number of deaths in India. On average, seven accidents were reported each month in manufacturing industries, killing a total of 162 workers, many of them precarious or migrant.

Small, unregistered factories are often the worst affected by accidents at work. Moreover, the government has changed workplace inspection protocols to make the process easier for companies. While inspectors are currently responsible for monitoring and enforcing safety regulations, their role will change to that of mediators under the new codes. Experts believe this will make it even less likely that factory owners will make worker safety and social security a priority (Source: BBC).

Uzbekistan

The ILO has announced that Uzbek cotton is free of systemic child labour and forced labour in 2022. The country was put under the spotlight in 2015 when many people, including civil servants and students of all ages, were forced to work in the cotton fields for the annual autumn harvest.

The authorities expected the population to mobilise to meet the state harvest quotas, a system inherited from the Soviet period. With the new leader coming to power in 2016, the situation improved, particularly following intense boycotts by companies and states such as the United States.

Under the leadership of President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, the country has embarked on reforms that include the modernisation of the country’s old agricultural economic model and the eradication of child labour and forced labour in the annual cotton harvest that previously prevailed (Source: Business & Human Rights Resource Centre).

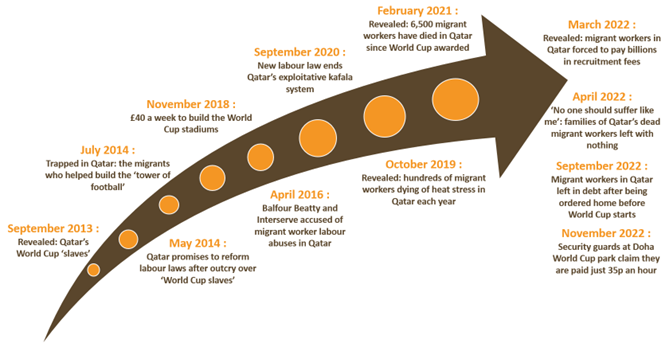

Quatar

The World Cup was hosted by Qatar for the 2022 edition. From the awarding to Qatar in 2010 to the final on 18 December 2022 – on the World Migrants Day as well as the national day – there have been numerous scandals surrounding the tournament. The Guardian has looked back at more than a decade of stories covering the conditions of migrant workers on Qatar’s outsized construction sites.

The controversies have highlighted the recruitment, working and living conditions of migrant workers who have come to Qatar to build infrastructure (Source: Vice). We were able to read about these workers and their families and better understand their backgrounds. It appears that migration is often associated with debts linked to recruitment costs, unhealthy housing, or long working hours for less pay, not to mention the tasks to be carried out in very hot weather. All this led to many deaths, accidents and mental illnesses. Back home, workers are unable to help their families and become a burden. This situation can lead to an increase in child labour forcing children to help their families. These are stories that can be found in other migration corridors.

The controversies of this World Cup can be found in another area: the manufacture of equipment. Sialkot, a city in North-Eastern Pakistan, produces about 70% of the world’s supply of footballs, including Adidas’ Al Rihla, the official ball of the 2022 World Cup in Qatar. About 60,000 people work in the football manufacturing business, about 8% of the city’s population. More than 80% of the footballs manufactured use hand stitching, a lengthy process that makes the ball more durable. Embroiderers earn $0.75 per ball, which is equivalent to three hours of work. Women sew, men test, and children have been banned from working on them since 1997. About 40 million footballs are bought each year, but sales are expected to jump during the World Cup (Source: Bloomberg).

United Kingdom

2022 saw a significant number of reports and press articles referring to cases of forced labour in the UK.

The health sector has been affected. Faced with a labour shortage in the sector, the UK is bringing in health workers from abroad. As a result, nurses recruited from Zimbabwe are reportedly trapped in “debt bondage” in the UK (Source: The Telegraph). Zimbabwe is in economic crisis and thousands of qualified health professionals are seeking employment abroad. However, employment agencies – often run by Zimbabweans in the UK and unregulated – are exploiting this situation by charging workers several thousand pounds to find them work in the UK. In addition, workers are subject to illegal deductions from their wages. As the UK seeks to sign an agreement to recruit Nepalese nurses, the situation of Zimbabweans should serve as a wake-up call. Nepalese employment agencies are already known for charging workers illegal fees that leave them in debt and in a vulnerable position (Source: The Guardian).

In the UK agricultural sector, Brexit and the war in Ukraine have led to a shortage of low-skilled migrant workers. Some employers are turning to the seasonal worker scheme. However, many Nepalese and Indonesians have found themselves thousands of pounds in debt after being sent home only weeks after arriving. They were recruited with the promise of working for six months, but arrived late in the season. As a result, they did not have enough time to earn the money to pay off their recruitment fees (Source: The Guardian).

In the textile sector in the Leicester industrial area, indecent working conditions continue to exist two years after the revelations. Workers interviewed said they were paid less than the minimum wage, could not take breaks, holidays or sick leave and were forced to work overtime (Source: The Guardian). Some reforms are needed, according to experts, such as better monitoring and enforcement of laws and fairer pricing for suppliers.

2022 saw a significant number of reports and press articles referring to cases of forced labour in the UK.

The health sector has been affected. Faced with a labour shortage in the sector, the UK is bringing in health workers from abroad. As a result, nurses recruited from Zimbabwe are reportedly trapped in “debt bondage” in the UK (Source: The Telegraph). Zimbabwe is in economic crisis and thousands of qualified health professionals are seeking employment abroad. However, employment agencies – often run by Zimbabweans in the UK and unregulated – are exploiting this situation by charging workers several thousand pounds to find them work in the UK. In addition, workers are subject to illegal deductions from their wages. As the UK seeks to sign an agreement to recruit Nepalese nurses, the situation of Zimbabweans should serve as a wake-up call. Nepalese employment agencies are already known for charging workers illegal fees that leave them in debt and in a vulnerable position (Source: The Guardian).

In the UK agricultural sector, Brexit and the war in Ukraine have led to a shortage of low-skilled migrant workers. Some employers are turning to the seasonal worker scheme. However, many Nepalese and Indonesians have found themselves thousands of pounds in debt after being sent home only weeks after arriving. They were recruited with the promise of working for six months, but arrived late in the season. As a result, they did not have enough time to earn the money to pay off their recruitment fees (Source: The Guardian).

In the textile sector in the Leicester industrial area, indecent working conditions continue to exist two years after the revelations. Workers interviewed said they were paid less than the minimum wage, could not take breaks, holidays or sick leave and were forced to work overtime (Source: The Guardian). Some reforms are needed, according to experts, such as better monitoring and enforcement of laws and fairer pricing for suppliers.

Switzerland

A popular initiative to make Swiss companies more accountable was rejected in November 2020. A counter-proposal was adopted by the Federal Council in early December 2021 and the measures are applied from 1 January 2022. Companies will have one year to comply with the law (Source: L’Agefi).

According to L’Agefi, large Swiss companies will, on the one hand, have to report on the risks generated by their activities in a spirit of transparency: they will have to draw up a report on environmental issues, social issues, personnel issues, respect for human rights and the fight against corruption. They will also have to present the measures they have adopted in these areas.

On the other hand, companies with risky activities will have to comply with extended due diligence obligations in the sensitive areas of child labour or minerals and metals from conflict zones or high-risk areas. The companies affected are those with more than 500 employees and a turnover of more than CHF 40 million over the last two years.

In the event of a breach of the new reporting obligations, a fine of up to CHF 100,000 is provided for.

Conclusion: what can we expect from 2023?

A strong commitment at European level

The first drafts of the laws on the European duty of care and on the ban on forced labour products have been published. The legislative process is expected to lead to the adoption of these laws in the course of 2023. It will then be necessary to adjust the existing laws in Germany, France and Finland, incorporate the provisions of the directives into national legislations and develop a harmonised European framework. The challenge will be to respond with a single voice in a multi-speed Europe.

The EU should continue to improve its tools to better enforce international labour standards in FTAs. The European Commission committed in June 2022 to have result-oriented and priority-based engagements with partner countries, to integrate more civil society participation and to put a stronger emphasis on implementation and enforcement.

Recovery still a long way off

2021 has seen an economic recovery following the lifting of many restrictions related to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, according to a new ILO report in January 2023, many countries have not recovered to pre-pandemic employment levels. Successive crises, including the war in Ukraine, have led to disruptions in supply chains and historic price increases. This will slow employment growth to only 1% (from 2.3% in 2022), and it will take several years to return to pre-2020 levels. Declining global demand, particularly in richer countries, could have consequences in low and middle income countries. In some of these countries, 20% of jobs depend on the global supply chain. The current global economic downturn is likely to force more workers into lower-quality, low-paid jobs without job security and social protection, exacerbating the inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, the persistent shortage of better opportunities for decent work is likely to worsen, the study says. Indeed, without the net of social protection, workers cannot remain unemployed, which will increase their vulnerability to exploitative situations