Looking back on the year 2022

Published on Feb 16, 2023

The year 2022 has been rich in events and developments in relation to Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8.7 to eradicate child labour and forced labour. In this retrospective, we looked back at the key landmarks of the year.

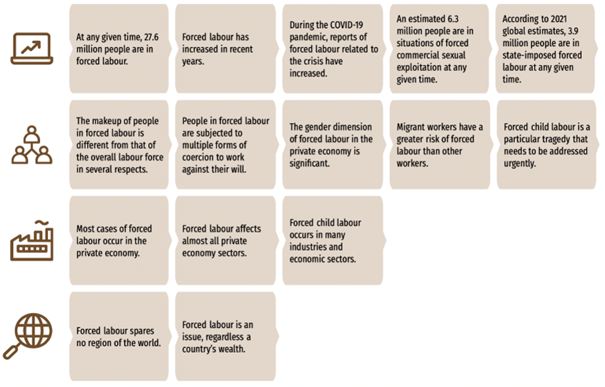

Forced labour: a growing number of victims

In September 2022, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in collaboration with the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and the Australian NGO Walk Free Foundation released the new Global Estimates of Modern Slavery.

Fifty million people worldwide would be living in modern slavery in 2021.

The report also shows that this number has increased significantly since the last estimates in 2017. Women and children remain disproportionately vulnerable to sexual exploitation and forced marriage, while men are more affected by forced labour.

Modern slavery is present in almost every country in the world and crosses ethnic, cultural and religious boundaries.

Behind the term “modern slavery”, the report takes into account:

- Forced labour in the private sector,

- Commercial sexual exploitation,

- Forced labour imposed by public authorities,

- Forced marriage.

Forced labour affects 28 million people, 17 million of whom are in the private sector.

Most cases of forced labour – 63% – occur in the private sector (other than sexual exploitation). State-imposed forced labour accounts for 14%. In addition, migrant workers are three times more likely to be subjected to forced labour than non-migrant workers.

More than half (52 per cent) of all forced labour cases occur in upper-middle and high-income countries. Asia and the Pacific account for more than half of the global total (15.1 million), followed by Europe and Central Asia (4.1 million), Africa (3.8 million), the Americas (3.6 million) and the Arab States (0.9 million). But this regional ranking changes considerably when forced labour is expressed with regard to the proportion of the population. Measured in this way, forced labour is highest in the Arab States (5.3 per thousand people); followed by Europe and Central Asia (4.4 per thousand), the Americas and Asia-Pacific (both 3.5 per thousand) and Africa (2.9 per thousand).

This increase in the number of victims can be explained by the many crises that have affected the world. The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly disrupted the worlds of work and of education. The growing number of armed conflicts is also a factor in increasing the risks. Finally, climate change and its disastrous and accelerating effects are increasing the vulnerability of populations.

These many crises lead people into extreme poverty, increase forced and unsafe migration, reduce the capacity of states to provide assistance and protection, and increase the incidence of gender-based violence. Workers have become more indebted, leading to an increase in debt bondage for some workers who do not have access to formal credit channels.

The main victims include the poor, especially those who are marginalised and discriminated, as well as informal and irregular workers without any protection.

These new estimates, which show a worsening of the situation, come a year after the publication Child Labour: Global estimates 2020, trends and the road forward. The ILO and UNICEF report also highlighted that the number of children in child labour had increased significantly.

ILO makes ‘health and safety’ a fundamental right

The 110th Session of the International Labour Conference held from 30 May to 9 June 2022 took the important decision to add safety and health to the fundamental principles and rights at work. This means that all ILO member states commit themselves to respect and promote the fundamental right to a safe and healthy working environment. This obligation applies even if member States have not ratified the fundamental Conventions in accordance with the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work adopted in 1998.

Occupational safety and health now becomes the 5th category of fundamental principles and rights at work alongside the existing ones:

- Freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining ;

- The elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labour;

- The effective abolition of child labour;

- The elimination of discrimination in employment and occupation.

Each fundamental principle is associated with the most relevant ILO Conventions. The new fundamental Conventions will be the Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155), and the Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 2006 (No. 187).

The recognition of the protection of workers’ health and safety as a fundamental principle was important, as it figured prominently among the constitutional objectives set out at the time of the establishment of the ILO. The preamble to the Constitution states that there is an urgent need to improve “the protection of workers against general and occupational diseases and accidents arising out of work”, among other aspects.

This decision comes against the background of an increasing number of work-related accidents and ill-health, on the one hand, and, an accelerated focus on mental health and the fight against violence and harassment in the workplace, on the other. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic, which has had profound consequences for humanity, has highlighted the importance of occupational safety and health.

Strengthening European legislative frameworks

In February 2022, the European Commission published its strategy to promote decent work in the world. This document brings together all the existing and future initiatives that are being defined by the European Union to implement decent work worldwide.

These include actions taken in the framework of sectoral policies (textiles, mining, agriculture and fisheries, etc.), trade agreements with third countries, guides for businesses and public purchasers, cooperations with international organisations and civil society, and legislative advances.

As far as legislation is concerned, two important texts were published in 2022 and will have to be voted on in 2023. These are the directive on corporate sustainability due diligence and a proposal for a regulation on the banning of forced labour products on the EU market.

EU-wide Duty of Care

The corporate sustainability due diligence continues its legislative path. It was announced by the European Commissioner for Justice in 2020 and the European Parliament adopted a resolution with recommendations to the European Commission in 2021.

On 23 February 2022, the European Commission adopted a proposal for a Directive on corporate sustainability due diligence at European level. On 1 December 2022, the Council of Europe adopted its negotiating position on the text. Following these general orientations, a negotiation will be initiated between the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament in the coming months.

At present, there are major differences between the proposals of the different EU bodies, be it the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union or the European Commission. These differences concern, among other things, the companies that will be subject to this law, the due diligence strategy to be adopted by companies, or the involvement of stakeholders. (For more information, read pages 25 to 32 of the RHSF Annual Report 2022)

In January 2022, the French National Assembly passed a resolution calling for “ambitious legislation on the duty of care for multinationals” at the European level. This resolution was carried by MPs Mireille Clapot and Dominique Potier, the latter of whom had brought forward the Duty of Vigilance law in 2017. The vote came at a time when France had just taken over the rotating presidency of the European Union and had listed the duty of care at European level as a priority.

Law banning products of forced labour

The European Parliament adopted on 9 June a resolution calling on the European Commission to develop legislation to ban the import and export of products manufactured or transported using forced labour.

In September 2022, the Commission published a proposal for a law, one year after President Ursula von der Leyen’s Union speech announcing it.

This legislation provides for a ban on all products placed on the EU market, manufactured in the EU for domestic consumption and export, and imported goods, without targeting specific companies or industries.

The term “product” is defined as one that can be valued in money and be part of a commercial transaction. The product may be extracted, harvested, manufactured at any stage of the supply chain.

The procedure would take place in several stages, starting with a preliminary phase when the authorities have reasonable grounds to suspect that the products have probably been manufactured with forced labour. If they determine that there is a well-founded fear of forced labour, they will proceed to the investigation phase, and thus decide whether or not to ban the product from the internal market.

Each Member State will have to set up an authority to carry out the procedures and the European Union will ensure consistency and coordination between each Member State. The European Commission will have to develop guides and tools to help local authorities succeed in their tasks.

Social protection

In the wake of the upheaval caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, the former ILO Director-General called for investment in universal, comprehensive, adequate and sustainable social protection systems, in accordance with human rights principles and international social security standards.

Indeed, many people are left without any social protection. A new report, ILO identified the gaps in social protection. Currently, only 47% of the world’s population is effectively covered by at least one social protection benefit. 4.1 billion people (53%) are not guaranteed an income by their national social protection system, despite the global expansion of social protection during the COVID-19 crisis. Disparities between regions of the world have widened further:

- Europe and Central Asia: 84% of people receive at least one social security benefit,

- The Americas: 64.3%,

- Asia and the Pacific: 44%,

- The Arab States: 40%,

- Africa: 17.4%.

Finally, only one in four children worldwide (26.4%) receives a social protection benefit.

Two countries have had major legislative advances:

- Since April 2022, employers in Singapore have been required to provide social protection covering health care for migrant workers living in dormitories or in the construction, shipbuilding and processing sectors. The aim is to provide affordable access to health care and reduce the risk of future epidemics. This rule will be part of the requirements for these workers to obtain or renew their work permits and passes. According to the Ministry of Labour, the programme will initially cover about one third of migrant workers, or more than 300,000 people.

- Morocco has begun to implement its project to generalise social protection. This generalisation will make it possible to preserve social equilibrium by fighting against precariousness, guaranteeing access to decent work, fighting against child labour and school drop-out, and limiting the rural exodus. In 2022, the effort focused on providing access to compulsory health insurance for all, which have enabled 22 million additional people to benefit from it. Subsequently, actions will be put in place to generalise access to family allowances, the pension scheme and unemployment benefits.

An international call to eliminate child labour

In May 2022, the 5th Global Conference on Child Labour was held in South Africa. This conference follows estimates in 2021 that showed an increase in child labour. Participants at the Conference – states, workers’ and employers’ representatives, businesses, academic institutions, civil society and UN agencies – committed themselves to greater efforts to eliminate child labour in a document called the “Durban Call to ACtion”.

The document contains commitment actions in six different areas:

- Make decent work a reality for adults and young people above the minimum age for work by accelerating multi-stakeholder efforts to eliminate child labour, with priority given to the worst forms of child labour.

- Ending child labour in agriculture.

- Strengthen the prevention and elimination of child labour, including its worst forms, forced labour, modern slavery and trafficking in persons, and the protection of survivors through data-driven and survivor-informed policy and programmatic responses.

- Realise children’s right to education and ensure universal access to free, compulsory, quality, equitable and inclusive education and training.

- Ensure universal access to social protection.

- Increase funding and international cooperation for the elimination of child labour and forced labour.

Conclusion: what can we expect from 2023?

A strong commitment at European level

The first drafts of the laws on the European duty of care and on the ban on forced labour products have been published. The legislative process is expected to lead to the adoption of these laws in the course of 2023. It will then be necessary to transpose the existing laws in Germany, France and Finland and develop a harmonised European framework. The challenge will be to respond with a single voice in a multi-speed Europe. The EU should continue to improve its tools to better enforce international labour standards in FTAs. The European Commission committed in June 2022 to have result-oriented and priority-based engagements with partner countries, to integrate more civil society participation and to put a stronger emphasis on implementation and enforcement.

Recovery still a long way off

2021 has seen an economic recovery following the lifting of many restrictions related to the Covid-19 pandemic. However, according to a new ILO report in January 2023, many countries have not recovered to pre-pandemic employment levels. Successive crises, including the war in Ukraine, have led to disruptions in supply chains and historic price increases. This will slow employment growth to only 1% (from 2.3% in 2022), and it will take several years to return to pre-2020 levels.

Declining global demand, particularly in richer countries, could have consequences in low and middle income countries. In some of these countries, 20% of jobs depend on the global supply chain. The current global economic downturn is likely to force more workers into lower-quality, low-paid jobs without job security and social protection, exacerbating the inequalities exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, the persistent shortage of better opportunities for decent work is likely to worsen, the study says. Indeed, without the social protection net, workers cannot remain unemployed, which will increase their vulnerability to exploitative situations.